When you begin writing a novel, one of the most powerful tools you can give yourself is a well-structured outline. It is more than a planning document—it becomes the blueprint that supports your characters, your world, and your narrative direction. A solid outline gives you clarity when the story expands, confidence when you revise, and stability when the writing gets difficult.

Start With the Core Elements: Character, Plot, and Setting

Before outlining, it helps to establish three foundational components: who your characters are, what they will experience, and where the story takes place. These elements form the scaffolding that everything else attaches to.

Begin by listing your characters and writing short biographies. Some characters may never make it into the final draft, but keep them anyway. When I began outlining The Burden of Honor, several early character sketches ended up unused for hundreds of pages—yet later became the seeds for supporting roles or future books. Nothing you create is wasted.

In a separate document, construct your setting. Whether your story takes place in a single city or across an entire kingdom, define it thoroughly. For The Burden of Honor, mapping key locations early—the Kellari capital, military garrisons, the Eidelind coastline—helped me avoid contradictions later and allowed the world to feel grounded. Once you know your world, placing your characters within it becomes much easier.

With character and setting established, you can turn your attention to shaping the plot.

Create a Raw Plot List

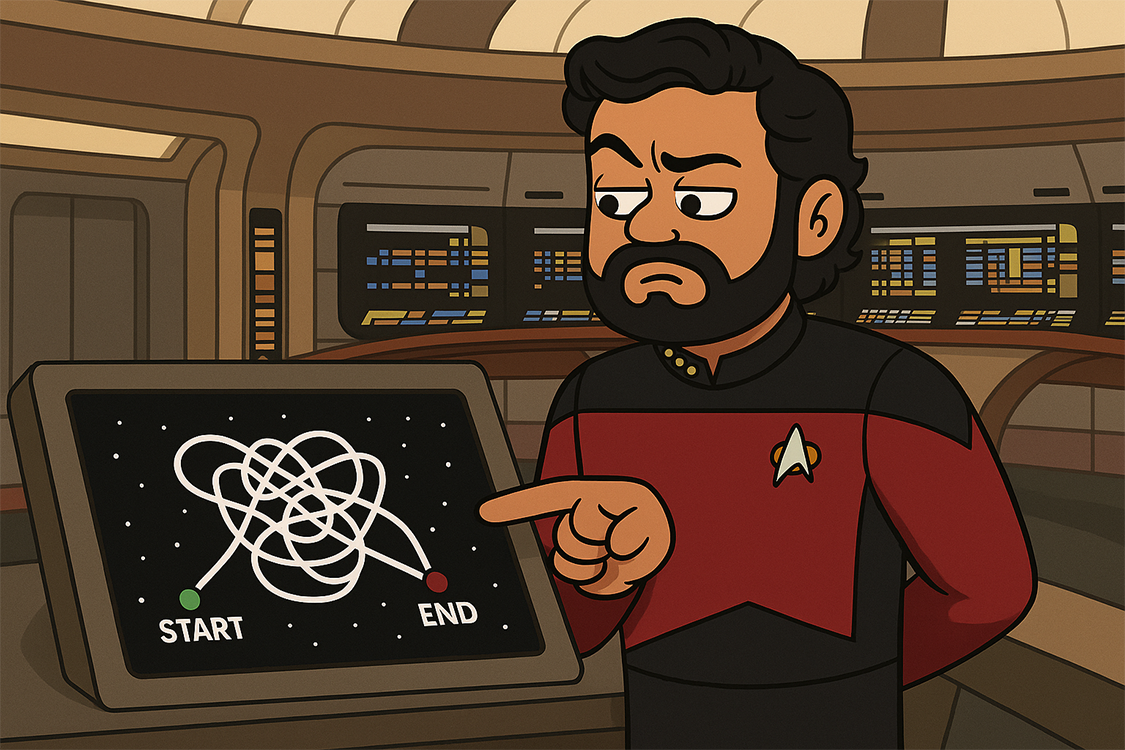

Your first outline pass should be simple: a numbered list of the major events in the story. These are not chapters, just the key moments you know need to happen. This version is intentionally broad and unrefined—the point is to capture the shape of the narrative, not the fine details.

When outlining The Burden of Honor, one of the earliest notes on this list was a moment I knew would define the book: Richard’s landing at Iron Beach. That wasn’t attached to a chapter or scene yet—it simply existed as a critical emotional beat I wanted to reach.

Sort Plot Points Into Chapters

Once you have the basic flow, start grouping related plot points into chapters. Chapter titles aren’t required yet, but purpose is. For each chapter, write a brief description explaining:

- what happens,

- whose point of view it follows, and

- what narrative shift or emotional movement occurs.

This is where your story begins to turn into something recognizable. In my own outline, Chapter 1 originally covered far more ground than it should have. Once broken into defined chapters with clear purposes, the pacing immediately improved, and the emotional beats had room to breathe.

Refine Chapters Into Scenes

Chapters are the broad strokes; scenes are the finer brushwork.

A scene is a contained event set in a specific place and moment. It allows your characters to move from another space and time within your setting. If a chapter takes place in a tavern, define the space, list who is present, and determine what must occur before the scene ends. Your chapter could end here or it could move to the next scene where your character returns home and reflects on the days events or interacts with a family member and talks about what ocurred in the previous scene. It’s all pushing the story along. In The Burden of Honor, scenes set in the Kellari council chamber benefited enormously from early scene outlines—I knew which political figures needed to speak, what tensions were present, and what the chapter needed to accomplish.

Some chapters may consist of a single scene. Others may require three or four. Outlining scenes helps you maintain focus and prevent chapters from expanding aimlessly.

Understand the Role of Beats

Inside each scene are beats, the smallest structural units of story. A beat represents a shift—emotional, narrative, or interpersonal. Beats carry the rhythm of your writing.

When outlining Richard’s enlistment and training, for example, I broke those early chapters into a series of emotional and developmental beats: his motivation to join, the uncertainty during recruitment, the shock of first exposure to military discipline, the camaraderie forming among trainees, and the gradual transformation from civilian to soldier. Identifying these beats ahead of time made it easier to shape his arc with clear momentum, ensuring that each moment carried purpose rather than feeling like a list of events.

Beats shape the experience of the story moment by moment.

A Complete Picture: High-Level and Low-Level Structure

After completing this process, you now have:

- a high-level narrative map,

- a detailed chapter structure,

- defined scenes,

- and beat-level emotional guidance.

Together with your character notes and worldbuilding documents, this becomes your “story bible”—your anchor throughout drafting and revision. If you prefer something without a religious undertone, call it your single source of truth or canon. This reference point becomes especially valuable as your story grows. The Burden of Honor began as a single novel but quickly expanded into material suitable for a trilogy and beyond; without a detailed outline, managing that expansion would have been chaotic.

The Outline Evolves as the Story Evolves

Your outline is a living document. It should adapt as your understanding of the story deepens.

My first draft of The Burden of Honor contained 23 chapters. By the time I reached the second draft, the outline had doubled. I discovered pacing issues, underdeveloped scenes, and opportunities to enrich character arcs. Entire chapters emerged during this refinement, some of them needed to be split into several chapters, including scenes that eventually shaped the core emotional trajectory of the novel.

Revising the outline allowed the story to grow into what it needed to be—not what I originally assumed it would be.

Outlines Can Have a Second Life

Do not underestimate the long-term value of your outline and materials. If your story expands into a series or universe, these notes become essential continuity tools. In some cases, authors eventually publish their worldbuilding documents, timelines, or narrative histories as companion works. Tolkien’s Silmarillion is perhaps the most famous example: a collection of notes and myths that became a foundational text of Middle-earth.

If you write long enough, your outlines may evolve into something similar—lore books, appendices, companion guides, or background materials that readers enjoy exploring alongside your main work. Have you ever become lost in a fandom wiki (or Wikipedia) just reading about all the little nuggets of lore that are a part of your favorite works? I can relate when it comes to World of Warcraft in that regard. I can’t get enough of the lore, the background of all the major characters, and so on.

Conclusion

An outline is not optional; it is essential. It provides structure when the story widens, clarity when revisions begin, and a dependable map when you find yourself deep within the narrative. Whether you intend to write a single novel or an expansive multi-book universe, a strong outline ensures you always understand where you are going and why.

It took me years—and several missteps—to truly appreciate this. Many of my professors in college and in high school emphasized the importance of outlining, and although I did not fully grasp the value at the time (and ocassionally scoffed at the mere suggestion… my goodness, younger me was awful), their guidance proved absolutely correct. The outline is the tool that turns inspiration into a finished manuscript and transforms scattered ideas into a coherent, resonant story.

As usual, thank you for taking the time to stop by my tiniest of tiny corners of the internet. Please leave a comment or shoot me a message on the contact page. I’m excited to share insights about writing, to reinforce why my English teachers and professors were wise beyond their years after personally learning the hard way, and of course to see if you interested in my stories!